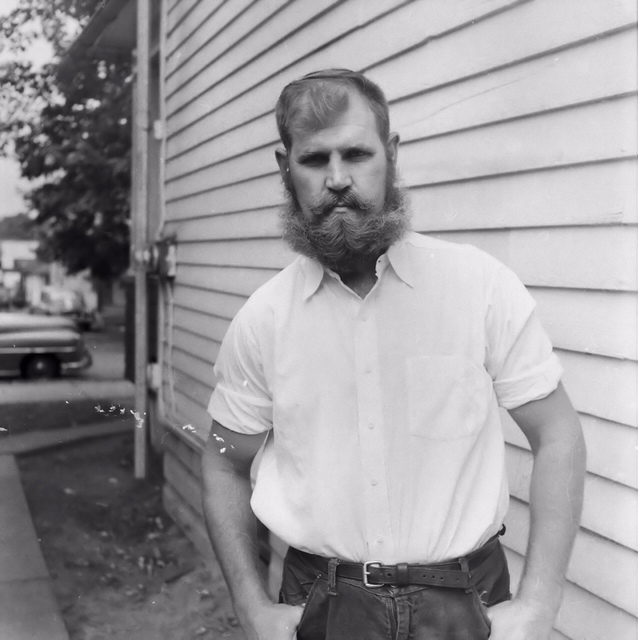

Jan 22, 1959 was just another day of work for Bill Hastie. He drove from his West Pittston home to Port Griffith for his dayshift stint at the Knox Mine.

Then, he stepped into a defining moment in Luzerne County history and became part of the end of deep coal mining in this area.

In the process, he managed to save a few souls.

“I remember the Knox. I remember those souls. Those poor men. God bless them,” Bill Hastie said last week.

His speech is slow. His words take on a tone of formality, very like speeches he made to groups in the past about the Knox Mine and the river that ran into it.

But many of the details of the day that changed his life, as well as the lives of dozens in the area, elude him. Often, when he tries to bring forth a name or describe a situation, he refers to it all as “complicated,” and “it would take too long to tell.”

Now 97 years old, Hastie suffered a stroke before Christmas. Now, with the help of doctors, nurses, therapists and caring staff at the Wilkes Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center, he works to rebuild his memory.

“He has good days and bad days,” said Trevor Hastie, one of Bill’s four children. “On some days, he seems to be able to remember some things. On other days, it’s just not there.”

Somewhere in Hastie’s memory is that day on the banks of the Susquehanna River. Just before noon, water from the river breached the ceiling of the mine that extended well under the river. It roared into the mine where close to 100 men were working.

“That was a dangerous mine,” he said.

The Knox Coal Company was one of many “contract mining” companies in the area that leased a mine from a larger coal company. In this case, it was the Pennsylvania Coal Company. Officials in both chose to ignore mapped “stop lines,” indicating where mining shouldn’t take place as well as the state law that prohibited mining within 35 feet of a riverbed. In the case of the River Slope mine, only about a foot and a half of rock and gravel separated miners from the Susquehanna.

“This was not a high-class company,” Hastie recalled. “They didn’t want to invest a lot of money. Just wanted to take money out.”

According to historical reports, when the water came, nearly 10.4 billion – yes, with a B – gallons poured into the mine. Men were trapped, surprised by the force of the cold, rushing water.

Some of the men underground were able to escape on their own, 33 others got to elevator lifts and were able to be pulled out. Forty-five were trapped deep in the mine.

Twelve never made it out.

Their names are inscribed on a monument near the Baloga Funeral Home in Jenkins Township and each year there is a memorial service for them.

This year, as part of Mining History Month, there will be a special presentation, “The Knox Mine Disaster Commemoration” at the Anthracite Heritage Museum in Scranton Saturday. Hastie will be given a special tribute at that presentation as the last living survivor of the disaster.

One afternoon last week, Hastie recalled a few things and was able to talk a bit about the day.

He said there was “lots of noise. Sirens. Alarms. The sound of the water. It was so loud.”

He recalls families at the mine, waiting to hear news of their husbands, fathers or brothers who were at work

“My family wasn’t there,” he said. “They couldn’t come all the way from West Pittston.

“One of the complications was that they had to endanger a number of men just to rescue the men who were already on shift. Men already working were objects of danger,” he said. “Water was coming in and blocking some of the ways out. They were battling the river.”

According to Hastie’s daughter, Megan, after Hastie encountered Amedeo Pancotti, who had just scrambled out of the Eagle Air Shaft, Hastie obtained rope to assist other men still trapped at the bottom of the Eagle Air Shaft.

He couldn’t recall the names of some of the men credited with helping. Men like Joe Stella who took two hours to lead seven men to the Eagle air shaft just north of the breach. Or like Myron Thomas, who took 26 others to the same shaft five hours later to be found by a rescue party.

In the fog that envelops his memory, Hastie does recall “super foreman Bob Groves” who “took great risk to get men out.

“I don’t know if he could swim,” Hastie said. “He came over from Scotland and I don’t think they have warm springs there to swim in.”

He talked about the Italians, lots of Italians, who worked to support their families.

But what stands out for Hastie is heroism.

“There were heroes. There were certain heroes who could’ve gotten out easily, but they stayed to help the ones more deeply located in the mine,” he said. There were heroes. I didn’t think I was a hero.”

In the months and years after the Knox Mine disaster and the subsequent investigations and trials, Hastie spoke to groups about the incident. He recalls speaking to the Wilkes-Barre Kiwanis and receiving high praise for his talk. He also worked with Dr. Bob Wolensky, historian and author who has penned several books on anthracite mining and its impact on the people who worked deep underground. Hastie and Wolensky co-authored “Anthracite Labor Wars,” which profiled miners’ efforts to unionize and get more control over their working conditions.

Hastie has a copy of Wolensky’s book, “The Knox Mine Disaster, January 22, 1959” on his bedside stand in the rehab center, a gift from his long-time friend.

Hastie heard that “someone is making a movie about all this” and he hopes he “will get to see it sometime to find out if they [the movie-makers] get it right.”

And, on Sunday, the actual anniversary of the disaster, there will be a memorial service at St. John the Evangelist Church in Pittston, followed by a public commemoration at the historical monument and then a walk to the mine disaster site.

This year, for the first time, Hastie won’t be at the services or the ceremonies, nor will he take the walk to the mine.